The Hermeneutical Teeter-Totter: Balancing Biblical Interpretation with the Global and Historic Church

An image for those of us who desire to faithfully interpret the Bible without a Teaching Magisterium located in Rome.

How can churches like mine—non-denominational and broadly Protestant evangelical-ish—have assurance that they both receive authority from “the Church” and possess a somewhat accurate biblical interpretation? What keeps us from teaching crazy doctrines or just a little off-based theology?

For many Protestant churches—especially those with zero denominational ties—the interpretation of the Bible essentially lies with the primary teaching voice. While most churches like this reject the papacy, it’s pretty clear most of us functionally include one. Instead of “Pope” they just call them “Lead Pastor.” I don’t disagree with this move (as my job title should reveal). In fact, as a Protestant, I think this can be a much healthier model than the teaching Magisterium structure from the Catholics. It’s one of the main reasons I happily stay Protestant. To have a few faithful, skilled, and trained people “rightly handling the word of truth” seems to be what was going on in Ephesus, Laodicea, and Corinth anyways (2 Timothy 2:14-16).

Nevertheless, I think we should be looking for ways to secure this ecclesiology: how can low-church, non-denominational communities develop a healthy communal hermeneutic? Put another way, how can all of our churches answer this question: from where do you get your interpretive tools? How do you come to your interpretations of Scripture? As I said, for many, many churches, they answer these important questions with a leader’s name: “Well, this is what so-and-so taught. Here’s his sermon from 2018 on that subject.”

Again, there’s actually something good about that. Every Protestant community can and should have 1-2 deep Bible nerds who do their homework, remain humble, and have clear thinking on theology that they received from trained, educated people. After all, the Bible is a strange book and church history is long and complicated. Someone in the church should be “a card-carrying Bible nerd,” as my friend Tim Mackie likes to say. Basically, if you don’t have a Pope, you should have a little, lowercase pope. There should be a primary voice, a go-to leader whose job it is to know the word and clearly divide it—the way Paul instructed his protégé Timothy (2 Timothy 2:15 3:16-17, 4:1-5).

At our church, I’m interested in broadening this to my pastoral team and my elders—to have the theological values held by all of us, as much as we are able. To be sure, these values are from me and I led our teaching team and elders through this. I’m taking the responsibility of the initiative, but I long for all of us to carry these together. I want us all to have an appeal so we can all say, “This is how we read the Bible and how we got to our conclusions.”

To start, we formed a commitment about what we think Scripture is and what it does. The confession Imago Dei has used is the French Confession (1559):

“We believe that the Word contained in these books (66 books of the Bible) has proceeded from God, and receives its authority from Him alone, and not from humans. And inasmuch as it is the rule of all truth, containing all that is necessary for the service of God and for our salvation, it is not lawful for people, nor even for angels, to add to it, to take away from it, or to change it. Therefore it follows that no authority, whether of history, or custom, or human wisdom, or judgments, or proclamations, or edicts, or decrees, or councils, or visions, or miracles, should be opposed to these Holy Scriptures, but, on the contrary, all things should be examined, regulated, and reformed according to them.”

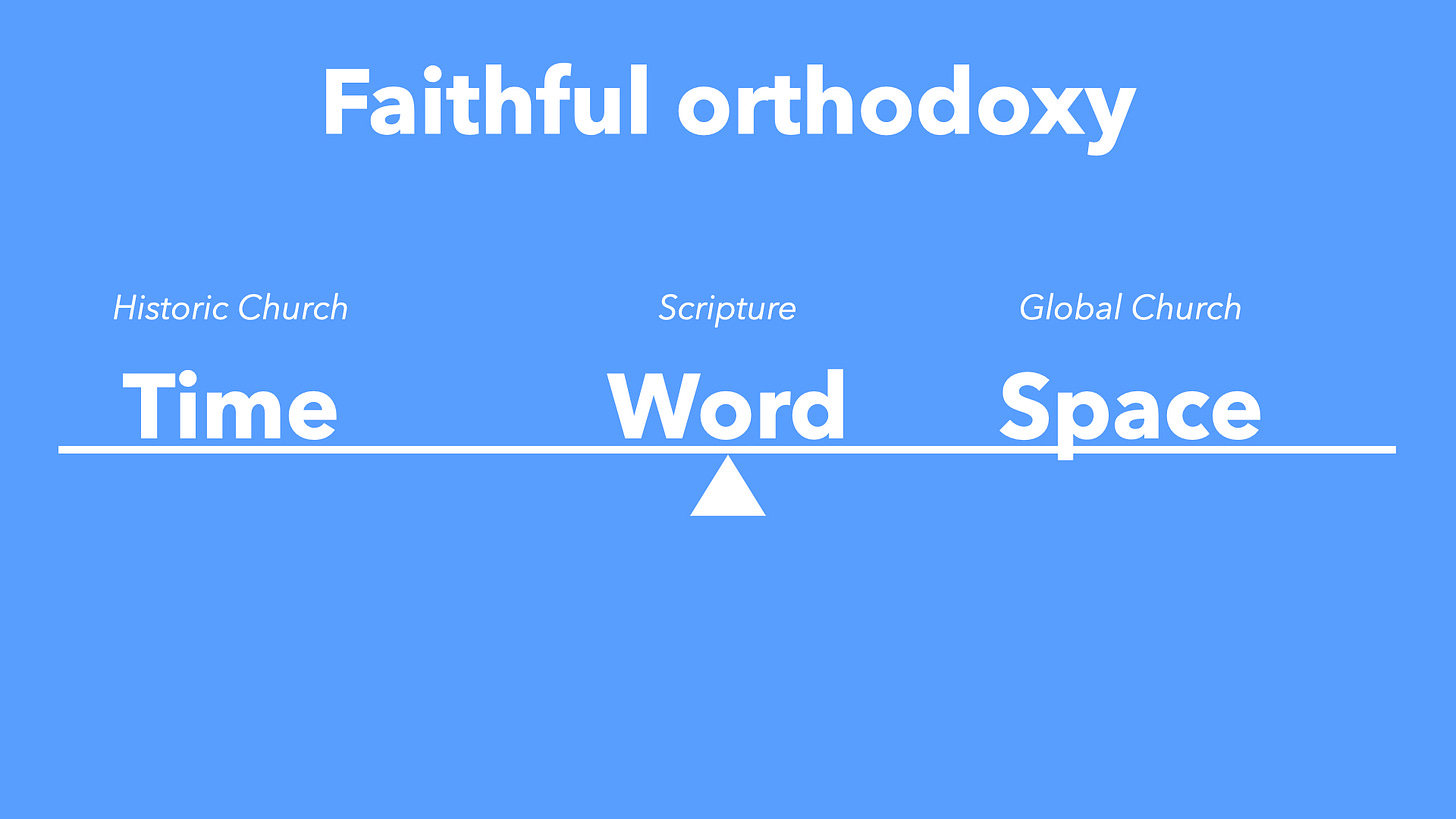

We also major with the BibleProject (our neighbors here on 13th and Ankeny) and use their “Paradigms” for answering the question, “What even is the Bible and how should we approach it?” From this place, then, we ask, “how do we interpret what we’ve agreed to above?” This is where the teeter-totter comes in: a way to balance our centrality and authority we place in the word of God with healthy interpretation. Here it is:

This is the teeter-totter. Pretty great Keynote work by me, huh? Imagine the center of the teeter-totter as our conviction from the French Confession: Scripture is our authority and our center. But “rightly handling the word of truth” is a balancing act (hence the image).

For me, “the Church” is the balancing community by which we interpret Scripture. Some call this “tradition,” and I’m also OK with that, if you want to use that. The Church created Scripture, canonized it, and allows it to be shaped by it across time and space. I disagree with Protestants who have rejected “the Church” as authoritative and quickly and only use the Bible. I only disagree with them because they are disingenuous. Their idea of “sola Scriptura” is more like “solo Scriptura,” where they live in a fantasy that you can read the Bible “individually” or “on a desert island” (see my longer criticism on that thinking here). No one reads Scripture on a desert island and the Bible wasn’t written on one.

The Bible is always interpreted by the Church that canonized it. In this way, and through this paradigm, I hope to return a Protestant vision of the Church as authoritative. The truth is that it is not either Scripture or Tradition, but Scripture and Tradition—the Word and the Church—that produces a healthy interpretation. Both the Bible and the Church hold authority for us, the faithful saints in Christ. I just don’t think the Church’s authority necessitates a Magisterium and a Pope over every local ekklesia or “assembly” of Christians in any given city.

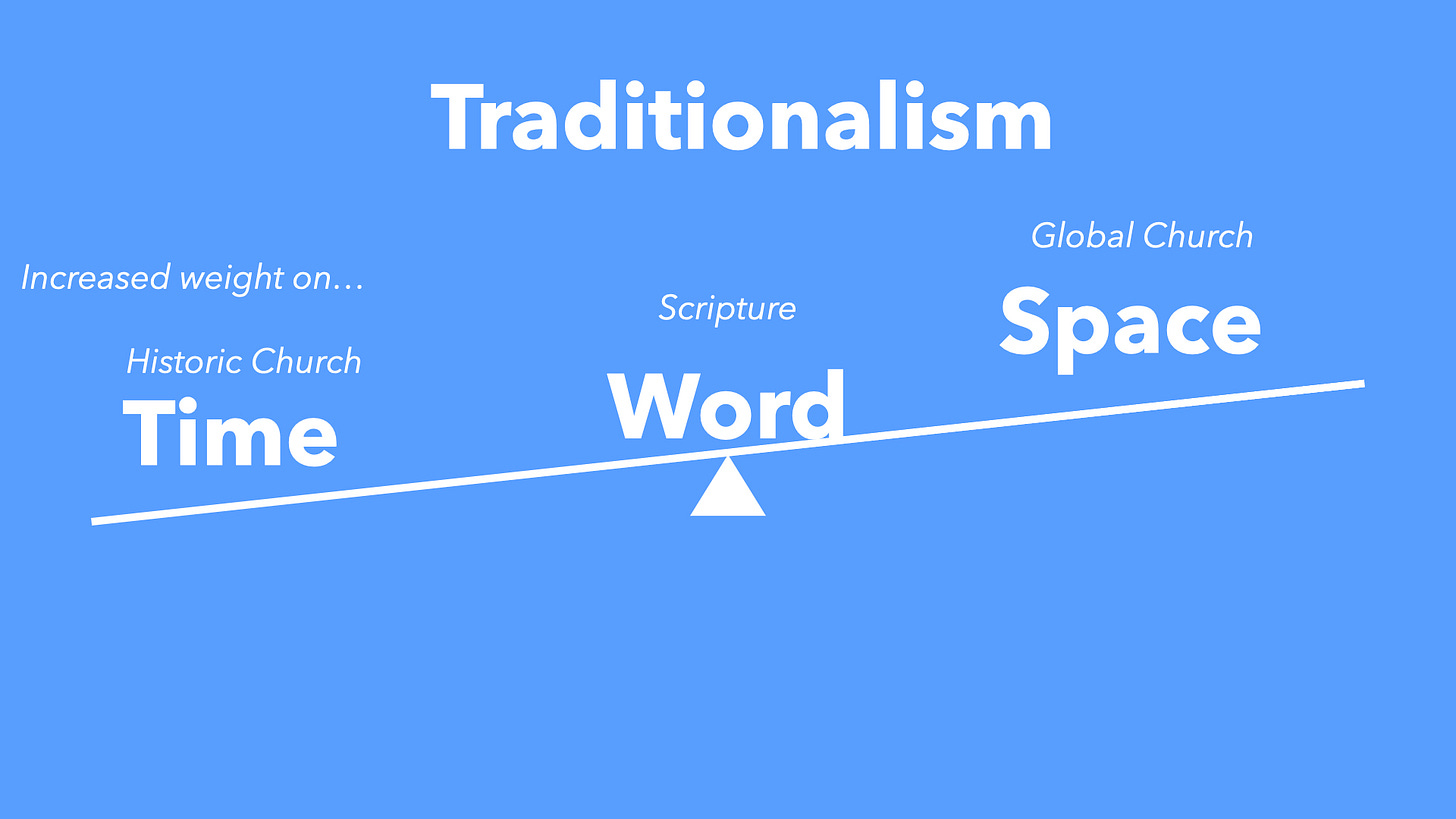

That’s what happens when we increase weight on the “Historic Church.” When put too much weight on the traditions of man, we get rigid traditionalism that either cannot change or makes no sense to the local context. A lot of Catholic theology ends up here (in my opinion) as doctrinal development of Mariology, transubstantiation, and purgatory have gone unchecked and unbalanced for too long. When we put too much weight on the Historic Church, we create theological bubbles that we protect with institutional power, not allowing the global nature of our faith to influence and correct our culture. The Church can quickly become how the Catholics appear to John Mulaney: “our weird Italian religion.”

We need the Global Church to balance this out. By “Global Church” I mean the ecumenical Bride of Jesus across the planet in different denominations and cultures. I mean that every Protestant Church can and should balance out Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Puritan, Coptic, and other traditions with their own reading of the text. We also must hear the modern church in Africa, our brothers and sisters writing in China, or publishing in Latin America. All of this is the “Global” aspect of interpretation necessary. If our reading of the text only exists inside American, White Evangelicalism, I’m afraid our interpretation is inaccurate at best and dangerous at worse.

But loving and reading the Historic Church—what the people of God have believed across time—balances us out of compromise or wishy-washy “borrowing” of theology so as to create an ecclesiological buffet with no firm center and zero flavor. This kind of compromise removes our Protestant convictions and our own ability to close the open mind on some firm beliefs. We can’t go on “assessing” and “seeking nuance” or we will never be able to boldly proclaim the gospel with confidence from the time and space God has placed our churches. We’re not creating a synthesis and we’re not becoming syncretists or anemic ecumenical pseudo-priests. We’re convictional Protestant and that means there’s a kind of historical reading of our theology that will lean that direction.

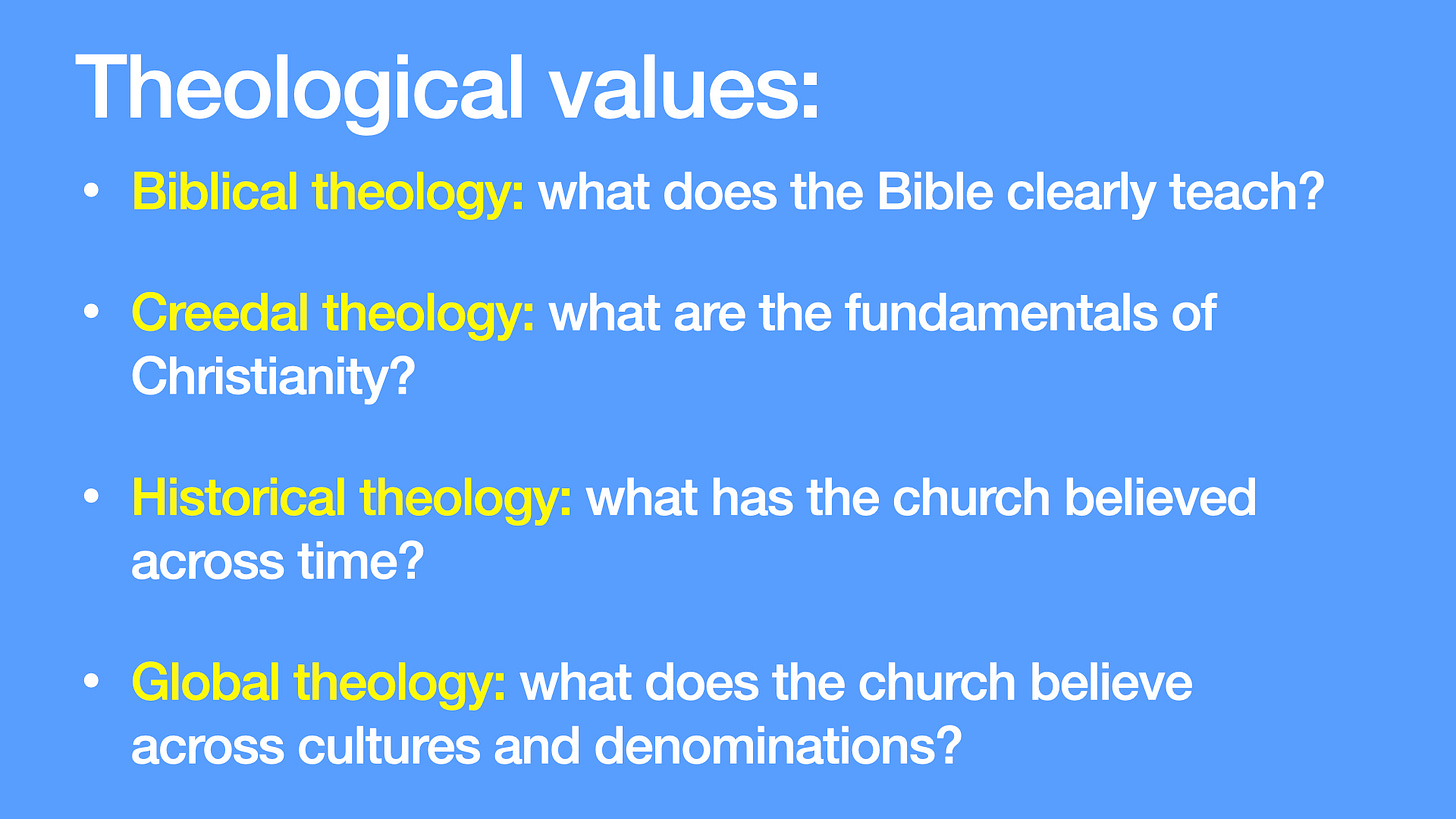

This is far from perfect, but it has allowed my pastoral-teaching team and elders to have a solid conversation about how we read the Bible and come to theological conclusions. It’s led us to develop “theological values” that tell us “what we hold dear together” when thinking about God. These considerations are then taking into our key theological distinctions. When we tell people why we came to those conclusions, we want to run them through this grid, and when we respectfully disagree, we want a basis upon which to have a fruitful discussion. Here are our theological values held with our pastors and elders that we share with our Covenant Community (our articulation of what many churches call “membership”):

From these questions written above, we will seek theological conclusions. Obviously, there’s tons in this to explain and set in our context. I have whole slide decks for each of these bullet points (perhaps to share in another post), but for now this will show a frame of reference for how to think through biblical interpretation in a non-denominational setting.

Isn’t your well articulated essay the same way the magisterium works? I think Im missing the difference in your distinctions.

Really well and concisely said. Thanks.