The Sounds of Advent: Blind Connie Williams, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord."

How can music help us understand the depths of Advent this year? And how can a poor, blind blues singer from Philadelphia lead us to the good news of Jesus this year?

“Advent begins in the dark. Anyone that tells you otherwise is living in denial.”

-Fleming Rutledge, Advent: The Once and Future Coming of Jesus Christ

“I can see everybody's mother, can't see mine.”

- Blind Connie Williams

*During Advent, I’m going to write a bit about how different musicians can offer perspective on the season of Advent in a series called “The Sounds of Advent.”

Christmastime is a different experience than Advent. Christmastime—and, yes, it is being spelled here in the traditional, one-word form—is a season of bright bulbs, glee, and glimmer. It is a time when nostalgia is summoned in order to put grief to bed, when our memories selectively edit holidays of past that certainly were not as cheery and warm as our brains have reconstructed them to be.

Christmastime is lonely for many people, and the assault of “Christmas cheer” can be horribly depressing. But Christmastime has no mercy: the happy songs play over loudspeakers as mad shoppers fill their carts under the headache of florescent lights until one of us has a panic attack or decides to club someone with noise canceling headphones that are on sale for $129.

That’s Christmastime. It begins in a kind of lit-up, plastic world, anxious world.

The Church does not participate in Christmastime; we participate in Advent, a season darkly contrasting “the Holiday Season” promoted in the West. Our Christmas story doesn’t begin in the manger, with the apocryphal drummer boy blithely playing as the Magi bear gifts on that “Silent Night” (which it most certainly wasn’t). Advent begins with “the people who walked in darkness” (Isaiah 9:2, Matthew 4:16), with the people of Israel wandering without a shepherd, lost without a light. “Advent begins in the dark,” says Fleming Rutledge. Darkness is paralyzing; it is disorienting. This is where our season begins.

Advent is a season, then, that begins with spiritual blindness. It reminds us of what life is like without God—or of a life awaiting God’s arrival. But this blindness is not our inability to see God—no one can see God! Spiritual blindness is the inability to see everything else. Life without God is like blindness because life without God is the inability to see reality. St. Paul puts it this way: “The god of this age has blinded the minds of unbelievers, so that they cannot see the light of the gospel that displays the glory of Christ, who is the image of God” (2 Corinthians 4:4). This image rings all the more when you consider that the man who wrote this (Paul) was blinded and healed during his conversion experience (Acts 9:1-19). He knew what it felt like to have scales fall from his eyes so as to see reality for what it was by seeing reality in the light of the glory of Jesus.

I can’t imagine being blind. The people I have met who have no sight astound me with their courage. The strength it must take to take any step while you cannot see is wild to me. Which is why blind musicians have long fascinated me.

You can take your pick of the remarkably talented individuals who did not let their own impairment to stop them from playing. Instead, almost like a superpower, they harnessed their inability to see and multiplied their ability to hear. Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles, or José Feliciano. And I’m just naming the ones with dope Christmas albums.

These musicians seem to offer us a unique kind of insight into what it means to live in Advent. To live with hope when you cannot see. To experience glory without experiencing its primary effect. To offer the world something great even when you can’t experience all the great things the world offers yourself. Those who play beautiful music illuminate a whole part of our senses (hearing) while they fully lack another (sight).

Advent is a bit like this. It is a period of time where the church sits in tension of Christ’s once and future coming. We stand assuredly in the fact that God has come—and, in some ways, that sense is fully active. We know Christ has come and risen from the grave. But we still sit in a world of darkness, awaiting his return. We still are “blind” to what it is that God is doing. We must sing the songs of God to remind us of that which we cannot see, but can still hear.

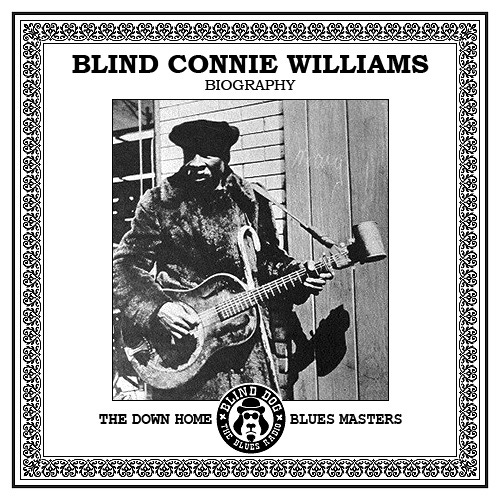

Blind Connie Williams was one of the great blind blues guitar players from the 1930s. His style remains essential to building out the future of rock/blues/R&B. Specifically, his guitar stylings set up the guitar playing of the great masters that would come after him. Without Connie, it’s hard to imagine Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Jimi Hendrix, and Eric Clapton.

Born in Florida, Blind Connie Williams was a street performer in Philadelphia, where he lived much of his life. His parents were migrant workers and his grandparents were slaves. He was a bluesman, but a man of faith who faithfully attended the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Maryland. He frequently traveled from Philadelphia to Harlem to play gospel music with the great Reverend Gary Davis. He was famous for a finger picking guitar style that utilized his thumb to drive the bass notes, uniquely allowing a two-fold rhythm of high-end notes and low-end rhythm. A few music writers credit him with what would become the roots of Rhythm & Blues guitar playing.

Not much else is known about Connie’s life. He played on the street: sometimes blues, but mostly his own reworked gospel songs that he played in his signature style like, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” a song of rich importance to the history of gospel music, written by Thomas A. Dorsey.

The song, as you can hear above, is a slow, painful song. The origin story of this song requires its own post. Dorsey wrote this song in suffering and for the sufferer. It’s no wonder why a poor, blind blues singer from Philadelphia was attracted to it. “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” is a song written in the darkness for a kind of darkness that still hopes—just like Advent.

And so, this blind man put a boogie to it and made it his own incredible version, which was (thankfully) captured by the inestimable Pete Welding. When Connie met Welding, he was an accordion player, mostly, because he could hear and feel the instrument better. But when Welding bought him his first guitar, some magic happened. Welding captured some of Connie’s playing on his label Testament Records in 1961, producing an amazing compilation that would appear years later as, Blind Connie Williams: Traditional Blues, Spirituals and Folksongs (1974). This album is so good and so precious that Spotify doesn’t have it. As always, the better platform, YouTube, does.

Here’s his version of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord”

There is something about this man and this song and this experience of his that teaches us about Advent. Walking in darkness, there is light. Connie Williams is physically in darkness as he sings this song of hope—a song of the precious Jesus accompanying us in our complete despair. The experience of gospel music does this kind of thing for me: it shows me (with remarkable clarity) the darkness and the glory. Gospel music does not sugar coat. There are no rose colored glasses and no silver linings. There is real darkness in the music.

And yet, gospel songs are filled to the fullness with glory—a weighty glory. Connie Williams lived his entire life in darkness and poverty. But he preferred to play these spiritual songs. Why? We don’t know for sure, but one certainly can take a good guess: there must have been something deeply good in them. Gospel music does this in a way the common contemporary Christian music just can’t. Contemporary Christian music tends to sound more like Christmastime than Advent. It sounds polished, settled, and soothing. Gospel music sounds desperate. And the old gospel roots music can grant us a better access point to the heart of Advent than any modern music can.

Gospel music was born in the darkness. The Atlantic Slave Trade remains perhaps the darkest time in Western history. Nothing has marked America more tragically and wickedly than our original sin of slavery and racism. What gospel music provides is a strange window into what God can do inside such evil: give sight to the blind, rescue the needy, give hope in despair.

Slavery is and was anti-God. It is a force of true darkness that still haunts this country. And it is so like the character of God to not remove himself from such darkness, but to involve himself inside of it, to enter in, to dwell among the wickedness and to comfort the sufferers as he judges the evildoers as he brings the evil thing into a redemptive good. God does not make evil, but he does get a hold of it in order to redeem it. I think this is gospel music’s prophetic power. It seems to signify the utter weakness of evil when it is in the hands of the Almighty. Advent tells us that God can give hope inside of hopelessness; God can be present in the darkness; the incorruptible divine can be in corruptible flesh. Blind Connie Williams seems to point to something like that. A blind man singing “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” with such honestly and integrity and creativity, seems to confront, even rebuke me in a good way: a blind man can see what I cannot. The Precious Lord I cannot see is taking my hand in the dark.

And so, we pray a great Advent prayer: “Father in Heaven, grant us eyes to see the light of the gospel during the darkness of our days.”

Brilliant, Chris! Blues songs seem so clearly connected to Psalms of Lament (like Ps. 88, for example: "darkness is my closest friend."). And it is when we are in these desperate straits, that God gives us light that cuts through our darkness. Thanks for introducing me to Fleming Rutledge and Connie Williams! Can't wait for the next musician you feature...