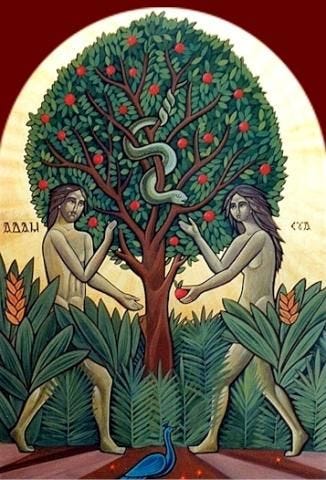

How did Adam and Eve know what death was before death entered the world?

The first couple is warned they will surely die if they eat of the forbidden fruit. How can they obey this order when they don't have a concept for the consequence of disobeying it?

Today’s post comes from a question I received by email. It’s a great question from one of my congregants after I preached a sermon entitled, “What do you want?” which was an exegesis of Genesis 3:1-7, which focused on the heart and human desire. This was his question he sent in:

“Since both those people [Adam and Eve] do not know what death is because nothing had died and there was nothing evil how would they know what evil is? This is sort of mystifying to me how God could tell them about evil and dying when they wouldn't know anything about it and according to the scriptures God doesn't explain what evil is or what death is.”

My response to his email is below:

Your question is wonderful and shows your keen eye on the scriptures. Thanks for sending this. I wonder if perhaps the answer is more simple than you think. If God told them they would die, we can assume a few possible options:

Adam and Eve knew what death was through the natural order of the creation they inhabited. There is no indication than animal suffering or plant death never happened. Some interpreters point to Genesis 2:5-6, which indicates the beginning of rain and plant life once a human could tend to the ground. Why would a human tend to the ground? To keep the plant life from dying and to keep it to eat. It is possible the Lord instructs the humans they will be like the dying plants if they eat from the tree.

The totality of God’s speech is not included in Genesis, only the speech we need to understand. By him mentioning the word “death” and the first couple clearly understanding it (as Eve repeats the command with little to no confusion in Genesis 3:2-3), we could assume either God taught them about death at another moment or that in that moment that word was understood. Not all occurrences are mentioned in Scripture, but rather all occurrences necessary for its interpretative message to be found.

Finally, knowledge of consequences is not a prerequisite for obedience. You know I have a five year old and an 18 month old. I spend lots of time giving commands and instructions to each of them. My son (5) and my daughter (1.5) have different understanding of consequences, but are often given the same commands. For example, I tell both of them they cannot touch the stove. My son understands why he can’t touch the stove because he understands what touching something hot can do. But he has never actually been burnt, nor does he understand the sensation of it and he even has yet to see someone get burned by the stove. For all he knows, being burned may not be so bad! But why does he obey? He obeys because he trusts my judgement more than his—and trusts that by obeying me his life will be free from pain (at his best and in ideal situations…kids definitely disobey). The precise nature of “the fall” of Adam and Eve is a rebellion against this trust. They began to trust their own judgement over God’s judgements as revealed in his command.

An important primer on an “angelic fall theodicy”

No matter how we understand it, I think your insight is important as it underscores the interpretation of an "angelic fall theodicy,” which is the interpretation I hold to regarding Genesis 3 (a longer explanation of this view is done well by Dr. Gavin Ortlund here). I believe that evil was present in the world before Genesis 3:1. The serpent’s presence and strange, sudden arrival “on the scene” reveals this, along with various other Old Testament passages about the “unseen realm,” as Dr. Michael Heiser puts it (Deuteronomy 32:7-14 being key). Satan and angelic beings rebelled against God and his heavenly hosts before humankind sinned. In other words, there was an “angelic fall” before a human one, and the fallen angels (demons) tempted humankind to follow their way of rebelling against Yahweh.

The entrance of evil is, then, the result of a rebellious group of angelic beings. In this view, evil is not invented by God. Evil is that which opposes and rebels against God, which leads to the unleashing of God’s great enemies on his good world: Satan, Sin, and Death or, the World, the Flesh, and the Devil. Make no mistake, God has enemies. In this view, God does not originate or create evil, but rather superintends over it and constantly takes evil into his own hands to re-work it for his good—to “re-intend” the intentions of evil for his redemptive purposes.

This is, essentially, the entire message of Genesis. Joseph sums it up well in the final chapter of the book. In response to the groveling of his brothers after their grave sins and works of wickedness, we read this:

19 But Joseph said to them, “Don’t be afraid. Am I in the place of God? 20 You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives. 21 So then, don’t be afraid. I will provide for you and your children.” And he reassured them and spoke kindly to them.

-Genesis 50:19-21 (emphasis mine)

In Tim Keller’s words, “God gives Satan just enough rope to hang himself.” God “out-intends” or “re-intends” the intentions of evil. Unafraid of them, God takes the rebellious forces of wickedness and reworks and outworks their intent to become His own.

“An enemy did this”

There’s also a very important parable about this in Matthew 13:24-30, which was pointed out to me by Greg Boyd in his book Satan and the Problem of Evil. I don’t know why it’s not spoken of more and looked at more carefully. I rarely hear sermons on it (we’ll preach on this in July at Imago Dei). I rarely hear it referenced when people talking about “the problem of evil” and yet it might be the most important passage when considering it. Jesus’ own interpretation of that parable in the ensuing verses confirms this (Matthew 13:36-43).

God did not invent evil nor did he bring it into the world. It is the disgusting outgrowth of an angelic rebellion that influenced and now holds captive the human race. It is the power that enslaves us, rendering us helpless to become the good people we claim we can be and yet constantly fail to become. “Sin is not [only] something we commit; it is something we…are in.”1

The grave dangers of this world—the “wrath of God”—that we experience all too commonly are the varying results of a rebellious invasion we have joined and that are enjoined to us in our flesh. Weeds.

When we see these “weeds” of this world and the terrors of our planet, we often say the opposite of the field owner in the Parable of the Weeds: “God did this!” we cry. Nearly everyone who witnesses suffering or experiences it suddenly becomes a Calvinist: God must be doing this, we think, How unfair! We assume the only thing powerful enough to enact evil is the God we were told was good. All the while, we’re told in this mysterious little story of Jesus, the complete reverse of our theology: “An enemy did this,” he says (Matthew 13:28).

Not everything that happens in this world is God’s will. This is why we must pray for his will to be done “on earth as it is in heaven,” as the Lord’s prayer commands us to pray. We must be led out of temptation, “delivered” from the “evil one” and led into the “land of the living.” We must be saved—there is no other route. It makes me think of a wonderful quote from David Bentley Hart in his masterful essay, “Tsunami and Theodicy” (which was adapted into a great book, The Doors of the Sea): “I can imagine none greater than the happy knowledge that when I see the death of a child I do not see the face of God, but the face of His enemy.”

All the more happy thought to know what God does to his enemies. Their sure and certain defeat is coming and our only hope is his grace, that we may not be swept away with the weeds, but held close as those for whom God came to harvest. He is—truly—our only hope.

I owe so much of my thinking on Sin to Fleming Rutledge in her masterful, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015), pgs. 162-204. This quote in particular comes from page 195.

I really love this, and agree we so often miss talking about these points about the nature of evil and sin. A good example i heard (and use often) is that cold and hot aren’t opposites. Cold is simply the absence of heat. Evil is the absence of God, a separation for all that is life! Great essay!

Chris—you should read that part of my book. There was a choice between two trees, as you well know. There is a long history in mythologies of mortality, demigods and humans. The choice is of knowledge, an explanation of reflective thought. There was an order not to touch either tree. Imagine that the choice was to eat from the tree of Life. It would not account for reflective thought, (DeCartes, “I think, therefore I am”). And, in fact, it is set up to blame the woman. It also explains, of course, pain in childbirth. If this seems extraordinarily irritating, please delete.