Every person who has good taste in music had a Stanley.

Stanley showed up in my life as my best friend Adam’s older brother. Adam and I were in fourth grade, but Stanley was seventeen. A giant to me, he played basketball for Cleveland High School and legally drove a car. This was enough to get my attention.

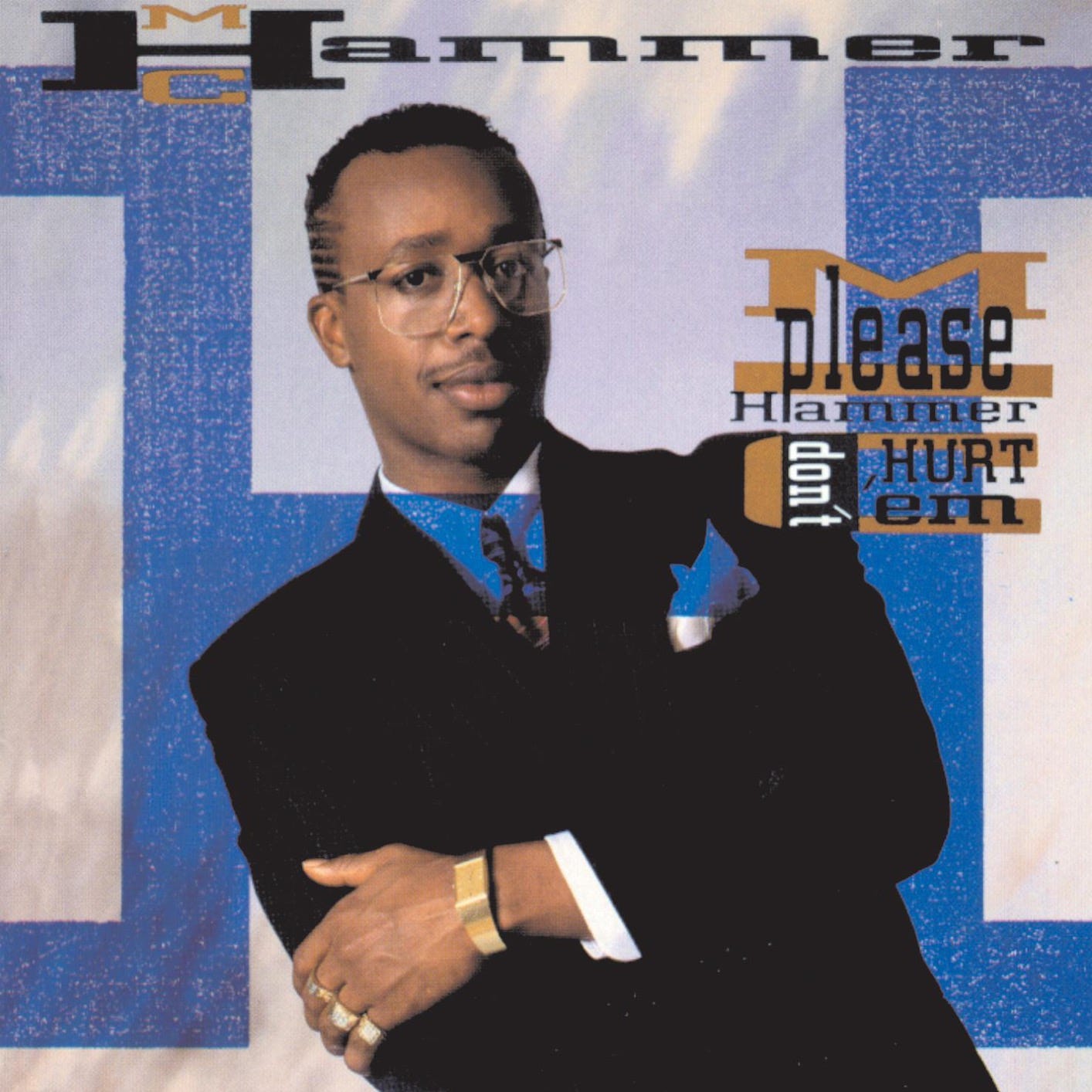

At the beginning of those years during 4th-8th grade, I wondered where Adam got all his cassette tapes. MC Hammer’s Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em, Beck’s Odelay, The Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready to Die, and the Cranberries’ No Need to Argue were suddenly in Adam’s boombox and we were transfixed. How did he get all this good stuff? Stanley.

I have this weird memory of Stanley babysitting us one night at my house when he asked me if I had ever heard of Violent Femmes. I was in sixth grade or so and too young to pretend to be cool. “No,” I said. And he pulled out their 1982 self-titled album and the stereo began to play “Blister in the Sun.” He closed his eyes and smiled. The good stuff. He left that CD at my house by accident and I never fessed up to possessing it.

Stanley was the first older kid in my life I remember turning me on to music I would have never found on my own or through my parents. My dad gave me a steady and very solid diet of American roots rock, the golden oldies (powered by 91.7 KISN), 50s-60s R&B, classic rock (powered by 92.3 KGON), lots of the blues, and even some of the good adult contemporary stuff from the likes of Jackson Brown, James Taylor, and Bonnie Raitt.

But everyone who loves good music needs that guy (or gal) whose just ahead of you, has a little more money than you, and can turn you on to the stuff your parents either don’t know about or don’t understand. They act as a portal. They are a conduit. They don’t even need to play an instrument or write music, but they know how to appreciate it. And they aren’t even commentators or critics—they’re tastemakers.

A tastemaker sets the standard for cultural input. They let you know what’s cool and what’s not. They are the authority, the ones who tell you what is good and what sucks. They define “the good stuff” for you and they can (with seeming divine authority) tell you to listen to an entire album and throw another in the garbage. They simply point at a record or hand you a tape and say those magic words: “Listen to this.” And you do.

In order to develop good taste, one needs a trustworthy tastemaker. If, as an adult, you are able to hold a broad array of music in your catalog, enjoy various genres, appreciate the classics while holding strong, contested opinions on the present, you probably had a tastemaker in your life showing you the way.

Tastemakers help you see that Little Richard is the father of all rock ‘n’ roll music and can’t get enough respect. They’ll tell you why Paul Simon’s Graceland works without being cultural appropriation, and they’ll explain why Eric Clapton only matters now because Sister Rosetta Tharpe learned to play the guitar decades before his extremely mediocre debut albums with Cream were ever released. They’ll tell you that you have to like jazz, but also how to start appreciating it (you don’t have to start with Miles Davis!), they’ll help you find good folk music and not the cheap crap, they give you Jay-Z’s Unplugged quickly and passionately alongside Zapp’s 1979 self-titled debut, they introduce you to the strange roots of country music that helps you see why Garth Brooks matters and it’s OK to cry when Stevie Nicks or John Prine sings, and they can explain why Tom Waits can help you appreciate Chopin.

And this brings me to theology.

Great theologians are discipled by theological tastemakers

For the past few years, I’ve been wondering what brings someone to become a compelling theological witness—a mind to be admired, a teacher worth listening to, a heart beholding the Glory—and I’ve come to realize one key, under-emphasized element of nearly every theologian/pastor I admire: they have great taste.

I don’t mean they like good theological resources, I mean they have learned to appreciate all valuable theological resources and are able to find value in their place in the Christian story while simultaneously being able to emphasize the most worthy materials. These folks have read widely, they have considered some of the riches of the Christian tradition, and have come to hold very strong convictions with incredible grace, humility, and understanding. They know the good stuff and they know the garbage. They have great taste.

Each of these theologians (and I’m just speaking now about people I know personally) have had tastemakers in their life: people who have showed them the ropes of theological influences, helped them understand the context, and handed them book after book. They were given the goods and can give it away now.

The best theologians had those tastemakers who helped them see the good stuff. These tastemakers not only told them that MLK is massively influenced by Reinhold Niebuhr, they handed over An Interpretation of Christian Ethics. They pointed out that Bonhoeffer was just making Karl Barth hit the ground of practical theology and they also gave them Dogmatics in Outline with Cost of Discipleship. Or they told them that if you love Tim Keller than you’d probably need read both C.S. Lewis and Jonathan Edwards, or know about how Dick Lucas was continuing the preaching work of D. Martyn Lloyd Jones. They probably handed out multiple copies of Howard Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited along with Frederick Douglass’ Narrative while pointing out these books probably would have never showed up without Gregory of Nyssa’s sermons on Ecclesiastes. They’re handing over the wave of incredible female scholarship between 1980s Beverly Gaventa up to today’s work from Amy Peeler or Cynthia Long Westafall and Lucy Peppiatt. They give you the big players of the Orthodox and the Catholics and then how all of this rolls us back to the departure of doctrine between Augustine and the Cappadocians and the women who influenced both sides—and tell you to read it all, including the weird stuff from Anthony of Egypt. They tell you about how Maximus the Confessor had his tongue cut out and it makes you excited to read On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ. They don’t dunk of Medieval theology, but instead show how Anselm might have had this all figured out before we ever did.

In other words, they give us the good stuff.

“Liking” something is different than appreciating it

And again, this doesn’t mean they necessarily like it all, but they’ve learned the art of appreciation. “Liking” is a trivial, surface-level enjoyment of a book or music. Appreciation is to count something worthy of being read, known, and considered with grace. The best theologians have great taste they got from being discipled by a tastemaker. Over time, they are able to decipher between the helpful and the unhelpful, and as they read the whole of it, are able to see orthodoxy and heresy with clarity. This allows them to share and demonstrate remarkable authority with tremendous grace.

The best theologians, then, become tastemakers after having multiple tastemakers in their own story. We all need people who help us hear the music. If we don’t, we’ll be enslaved to what we “like,” beholden to the first four bars and if they’re “catchy” (all terms that, in the end, mean absolutely nothing).

We need the tastemakers to help us see the value of the Thomists and the disciples of Bulgakov, of the Bavink lovers and the students of Watchman Nee and Aimee Semple McPherson, and the goodness of John Mark Comer/Dallas Willard/Richard Foster discipline-obsessed Christians with the grace-obsessed post-Lutherans like Fleming Rutledge or Gerhard O. Forde. It’s possible to have a deep love for Augustine and Basil; you can be on team Macrina and love Saint Monica. Trust me.

Without faithful biblical tastemakers, we become theological philistines, unable to have any kind of sophisticated appreciation of Christianity and only able to regurgitate things we think sounds good. We will be consigned to cheap imitations of recycled material instead of those who dwell deeply in the word with those who have gone before us. We need the good stuff. And we need people ahead of us or in a different cultural space than us who can give us the goods.

Filling in blank and blind spots

The first time I was in Gerry Breshears’ office, I left with a book. “Read this,” he told me after a three hour conversation to see just how much I knew and how far I could start ahead in seminary with advanced standing as I began (it wasn’t far at all). He put Water from a Deep Well: Christian Spirituality from Early Martyrs to Modern Missionaries by Gerald Sittser in my hand. He correctly identified where I was lacking in my theological taste. I was 25 and had only really read Augustine’s Confessions, Calvin’s Institutes, and Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises for any church history. “This will get you started in a key blank spot you have,” he said.

That book completely changed my life. Not only did I begin to read different books, I read all books differently after it. Sittser is a tastemaker and so is Breshears. They’ve had other people hand them the good stuff, so naturally, they hand others the same. That one book set my sights on church history in a whole new way…a journey I’m still on.

And then, about two years ago, when I was about to begin my current pastorate at Imago Dei, I found myself in Gerry Breshears’ office once again. He handed me Roger E. Olson’s Against Liberal Theology and told me to track down J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism. I read both simply because Gerry told me to.

Breshears has done this for me countless times with books from all across the spectrum of the evangelical theological tradition. It has helped me a ton. Each time he gives me a book, Gerry subtly and not-so-subtly shows me my gaps, corrects my tastes, and gives me the goods. And each time, he helped me hear the music.

I love the group chats, coffee meet ups, and after church conversations that keep the tastemaking going. I’m here for the Spotify link, the photo of a few records strewn across the floor, or a single book, sermon, or article with simple text: “You know about this?”

We need each other to find the good stuff. It’s not our opinions that are at stake, but our ability to hear the music. We need tastemakers to become one. We need Stanleys.

"extremely mediocre debut albums with Cream..." Much love and respect to Sister Tharpe but pastor, you need to come to Jesus! Lord, forgive him, he knows not what he speaks! 🙏🏼😉

I think this may be the strangest segue I have ever read: "...and they can explain why Tom Waits can help you appreciate Chopin. And this brings me to theology."

But, as usual, another masterful lesson by the great Chris Nye! Keep doing what you're doing brother.