The Sounds of Advent: Nina Simone, "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free" (Live at Montreux, 1976)

The High Priestess of Soul wrote some of her best music while battling personal darkness, but her cover of the Billy Taylor standard encapsulates her artistic vision, which is also richly theological.

“[Freedom] is just a feeling…you know it when it happens…I had a couple of times on stage when I felt free. That’s really something else…I’ll tell you what freedom means to me: no fear. No fear.”

-Nina Simone, interviewed by Peter Rodis

“Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.”

-2 Corinthians 3:17

*During Advent, I’m going to write a bit about how different musicians can offer perspective on the season in a series called “The Sounds of Advent.”

Nina Simone once tried to make a gun in her garage.

It was the night she ran out of her house, screaming and crying. She began putting pieces of scrap metal together to try to build a weapon that would kill what she hated and what she spent her whole life fearing. The High Priestess of Soul was ready to kill.

As erratic as this behavior sounds, it makes all the sense in the world when you know that this moment of mania happened on September 15, 1963, when white supremacists from the KKK terrorist group lit 19 sticks of dynamite, bombing the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The terrorist attack killed four little girls in the church’s basement: Addie Mae Collins (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11).

At this point in her life, Nina Simone already had enough to bear. Her entire musical career up to that point was defined by racism, sexism, abuse, and theft. A classically trained piano prodigy—a true musical genius—Simone was rejected from several institutions for being black. She gigged in clubs to make ends meet, taking up jazz by necessity because no white audiences wanted to see a woman that looked like her play Bach and Chopin. She was swindled by capitalist racists in the record industry at nearly every turn. On top of this, she was physically, verbally, sexually, and emotionally abused by several men through her life. Because of all this, she also suffered from a variety of mental illnesses—both diagnosed and undiagnosed.

And then four little black girls were killed in Alabama.

It was on this night that she went in her garage and started to make a weapon for war. Her husband was the one who said something that changed her mood and mind: “You don’t know how to kill people,” he said. All she had, he said to her, was her ability to sing and play. That was her weapon.1

As she tells it in her autobiography, this was when she went inside and wrote her most prophetic song, “Mississippi Goddam,” which, she says, fell out of her.

She wrote it in a matter of minutes. The rage, psychosis, and truth comes through in it (and perhaps most especially in the live renderings from Antibes in 1965). It sounds like the song of a woman who tried to make a gun only to fall on a piano (a piano she had already mastered by the age of 11): angry, lamenting, righteous, skilled, prophetic, proud, defeated, defiant, and all at once true.

The song went on to be banned by most white radio stations and shunned by the white record executives. But that wasn’t enough. The song has gone on to be one of the most important compositions throughout the Civil Rights Era.

But as important as “Mississippi Goddam” is, it’s not an Advent song—it’s a song of lament. Don’t get me wrong, lament has a place inside Advent, but for a lament song to be true to itself, it must stay in the dark. The beauty and gift of lament poetry in the Bible is that there is no foreseeable hope—no light in the dark. What a gift it is that God allows (encourages, maybe?) us to speak and sing from the inescapable darkness. That is the lament.

But Advent is about longing. We await God’s surprising arrival. As we reflect on the way in which he came as a child, we wait in eager anticipation of his Second Coming where he will come to set this broken world right. This is why we call it “Advent” (which means “arrival,” in Latin): we celebrate the once and future coming of Jesus Christ as salvation for the whole world.

If “Mississippi Goddam” is a song of lament, “I Wish I Knew How It Feels to be Free” is a song of longing.

The song was written by the composer Billy Taylor—a song he said he apparently wrote for his daughter. It’s a jazz standard that became a big hit for Nina on her (mostly) 1967 cover album Silk & Soul. It’s a great rendition and it captured the hearts of many in the Civil Rights Movement. Simone became a central figure in the struggle for black rights in America through both her songwriting and her advocacy. She even was neighbors with Malcom X at one point.

This is a song of delicate longing—a desire to exist in a way that seems unreachable.

I wish I could share

All the love that's in my heart

Remove all the doubts

That keep us apartI wish you could know

What it means to be me

Then you'd see and agree

That every man should be free

But the absolute best version of this song was only recently released to us. And it takes the song to a whole other level.

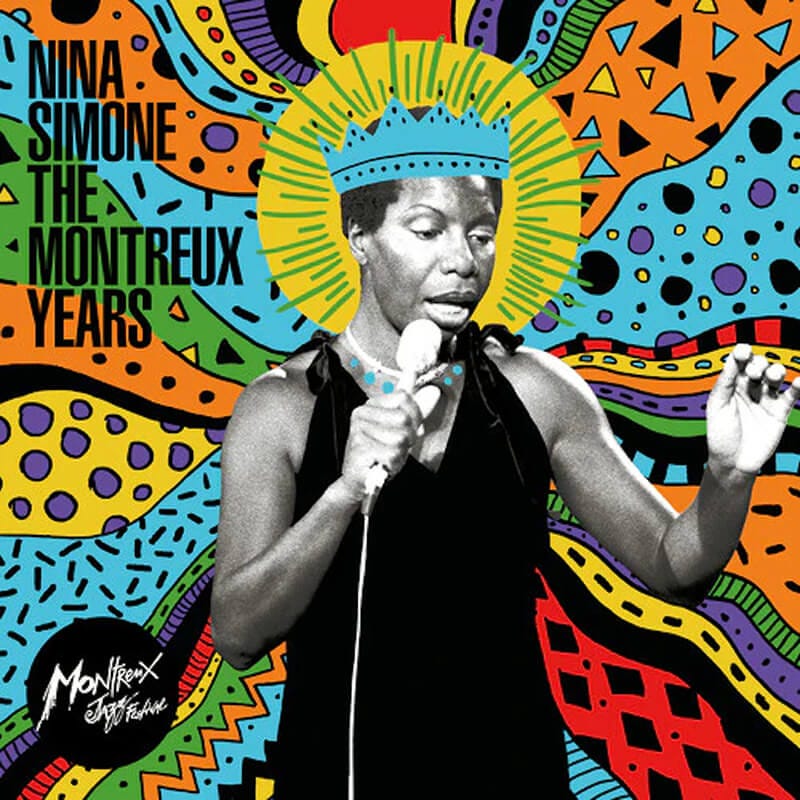

The version is from 1976, on a new release from BGM in April of 2021. The compilation features Simone’s years playing the Montreux Jazz festival, starting in 1968, just one year after she released the song upon which this essay is based. Her whole career can be understood, it seems, through “the Montreux years.”

And this 1976 version is just something else. Considering this is nearly a decade after Dr. King was shot and another decade into Simone’s own mental struggle and financial difficulties—the performance takes a new weight, a different sadness, but strangely a fresh hope too.

Please, I beg you, watch this performance with good headphones on:

The video captures the effortless nature with which she always performs. She is bouncing up and down, lifting her arms, steading her voice, all while she keeps the band locked in (her exclamation midway through, “Spirit’s movin’ now,” is such a great moment, along with her other lyrical ad libs near the end). Technically speaking, some of her runs and moves on the piano are so difficult, but you would never know. Like a Steph Curry three, she makes it look easy.

The song takes its time to get you there, but at the end, her piano cascades down and then back up as her voice follows (around the 4:44 mark). She tags the end, rattling off all the things she’s shed, only to exclaim—in the final line—the consummation of the song’s hope: “I KNOW! How it feels! To be free!”

There’s something about this performance that has always struck me as deeply Christian. The song holds both the desire to be free and the exclamation that we are. Its melody is happy, it’s lyrics are sad. The song begins with a desire and ends with a security. And through it all is the longing that comes with the Advent season: when will God come? When will we be free? Will we? Are we already?

And it’s really only in this 1976 version where you get a window into this song’s meaning for Simone. This was absolutely the Civil Rights anthem that it is, but it’s also a sort of personal testimony for her own inner life. Simone’s own hardships imprisoned her. Her mental illness stifled her career, her trauma haunted her in her own relationship with her daughter. She could be cruel. Something about this performance has a two-fold nature of its political and personal significance for the High Priestess of Soul.

A song that embraced the personal and political nature of hope reminds me a lot of Mary’s song at the start of her pregnancy, commonly referred to as the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55). Mary sings (personally) that God “has been mindful of the humble state of his servant,” and celebrates that political victory will be born certain and surprising: “He has brought down rulers from their thrones, but has lifted up the humble” (Luke 1:52).

God won’t free Israel and the world through a violent overthrow of the political regime. Instead, He’ll sink Rome with a cross. And that’s exactly what He did. The victory against evil and deadly empires doesn’t come through coercion and violence, but through the patient suffering of the saints. It’s surprising and it’s certain. It’s hope. It’s what it means to be free. The politics will fail us, but that doesn’t mean they won’t get their due. Justice is real. It’s coming from a cross.

Nina Simone’s mother was a preacher. She pastored in the United Methodist Church for nearly all of Simone’s upbringing. Like many soul artists of the 1960s, Nina’s entire life was shaped by church and gospel music. There’s no way to divorce her rich significance in American popular music from her experience as a preacher’s kid. There is also an element of church in this performance, of the Spirit moving. Just as Aretha Franklin’s father would say when many accused his daughter of “leaving the church.” No, he would kindly say, Aretha never left the church—she took the church with her.

I’m not sure Nina Simone ever got totally free. The rest of her life was, by all accounts, different levels of misery. She lived in Africa, was sued by the IRS, constantly struggled with money (was never really rich and was often very poor, even after massive success), and never had solid relationships around her. Famously, her own daughter struggled to stay near her and would eventually flee to America to escape her mom’s abuse. After years of pain, she died at 70 in France due to complications of breast cancer.

Nina’s 1976 Montreux performance gives me hope for her and for us, which is why I think about it during Advent. The desperate longing she showcases is something Jesus Christ seemed curiously attracted to. He was “amazed” at the centurion’s faith when he made a desperate plea for his servant (Matthew 8:5-13). He shut down crowds that tried to hide two needy blind men in Jericho. Hushing the noise, he asked them, “What do you want me to do for you?”

“Lord,” they answered, “we want our sight.”

Jesus had compassion on them and touched their eyes. Immediately they received their sight and followed him (Matthew 20:29-34).

The Bible is a book that, upon reading it, will fill you with the desire to be freed from this world and to pray to God for salvation. Just read Genesis and you’ll get desperate for God. You won’t feel great for a lot of chapters, but you will feel a strange hope, that no matter the gravity of our sin, God is able to rescue us.

Nina is no saint. From what we know she was abusive, cunning, and most certainly a liar. These things make sense when you hear of the trauma she endured and the mental illness that haunted her during the duration of her life. She just wanted to know what it feels like to be free.

And while we all may not have such drastic levels of trauma, I think all human beings have the longing Simone displays in the song. We all want to know what it feels like to be free. We’re captive to our own egos, tied down in this flesh, ruined by the sin done to us and that we do to others. We struggle with shame, addiction, anxiety, and depression. We are not predisposed to freedom, nor are we exactly sure how to achieve it. But we do know when we’ve got it. And just because we’re not predisposed to freedom, does not mean we were never made for it. It might, in fact, mean that we are.

“18 I consider that our present sufferings are not worth comparing with the glory that will be revealed in us. 19 For the creation waits in eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed. 20 For the creation was subjected to frustration, not by its own choice, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope 21 that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God.”

-Romans 8:18-21

Nina Simone and Stephen Cleary, I Put A Spell On You: The Autobiography Of Nina Simone (Da Capo Press, 2003).